By Philip //

In my late forties, I was doing very well in an academic career. I’d just published three important books, my teaching was going well, and I was asked to take up a leadership position in an interdisciplinary programme in my university. I had tenure, and with it, finally, job security until retirement. I knew that the last twenty years, when I’d put so much into my career, had been stressful, but I felt that the stress had actually driven me on to achieve more.

After I took up my new position, I found myself falling asleep at night, but then waking in the early morning, around 2 am, and being unable to go to sleep again. Thoughts about problems at work would go round and round in my head. When I did get up to go to work, I was tired, and there was something else that I later came to know as low mood.

I felt as though I was walking all the time through a very heavy, viscous liquid: every movement, every thought, was an effort. At work, I would shut my door and avoid other people as much as possible.

I’d try to focus, but found it impossible even to write basic emails, let alone do research or make plans. When I was scheduled to teach classes or chair a meeting, I found myself unaccountably nervous. I’d always felt a stage fright before such events, but this depth of my anxiety was new to me, and prevented me from focusing on anything else for the hour or so before the event would take place. I’d watch the clock in my office, trying to distract myself from the slow turning of its hands, but always coming back to watching it.

I didn’t know much about mental health issues at the time, and my partner encouraged me to see my GP. I was referred to a psychiatrist at NUH, and diagnosed with major depressive disorder. I was given two types of medication: Xanax, a benzodiazepine , to manage anxiety in the moment, and escitalopram, an SSRI, to treat depressants. My psychiatrist also introduced me to Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, and I worked with him and later another psychiatrist writing out thought records to challenge automatic negative thoughts that underlay my depression. Looking back, I’d say the medication helped buy me time, although I did feel emotionally blunted and distant from my surroundings. CBT did give me a feeling that I was doing something about the depression, but there were two problems with it. First, the psychiatrists tended to administer CBT in a very transactional manner, without much empathic listening. Second, some of the negative thoughts I had were actually quite rational: some of the pressure I felt at work was having to introduce, enforce, and defend new policies I didn’t agree with, but which had already been decided without my input.

I struggled on like this for two years, and then took a leave of absence from work with my partner. We spent some time in a different environment, outside of Singapore, and I began to see a psychologist, who came used a person-centred and Gestalt-influenced approach to counselling. She helped me to see the bigger picture. With medication and with CBT, I’d wanted to get a quick fix to carry on with my life as I’d lived it before. I remember very clearly one image she used.

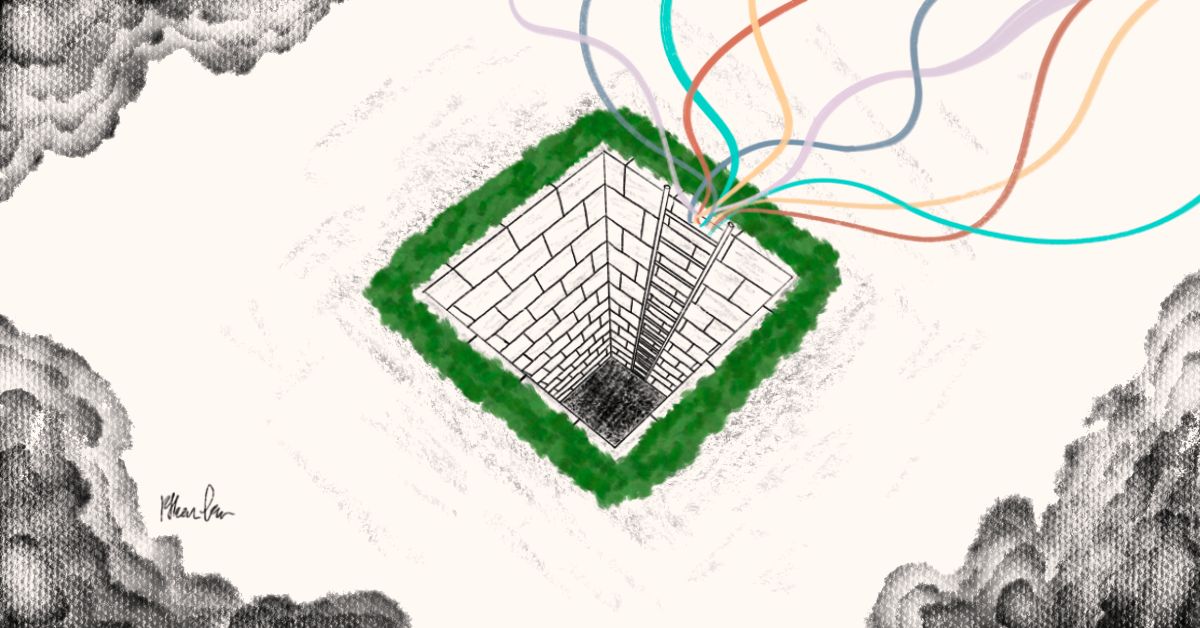

All my life, since I’d entered primary school, I’d been on a ladder, always climbing upwards, never looking back. I’d been driven by extrinsic markers of success. Would I still be climbing the ladder when I was seventy or eighty years old?

Some time, surely, I would need to get off. What might getting off look like? Would it really be so bad?

My psychologist helped me realise that, in narrative therapy terms,

I’d had a “thin story” of my life, gaining self-worth and affirmation from external markers of achievement.

When I came back to Singapore and to my job, I was kinder to myself. I focused more on teaching undergraduates, which I now realised was the most satisfying and meaningful part of my job. I moved to part-time work to give myself more time in my life for my partner, who had supported me through difficult times, for family, friends, and meaningful activities such as creative writing that I’d long neglected. Eventually, I left the university and retrained in counselling psychology. Depression never quite goes away. I find it’s always hiding from me, just out of sight, and if I’m not careful it reappears.

I find meditation and exercise important, but most importantly being part of communities in which I both care and am cared for.

I still have a toehold in he academic world, doing research at a slower pace, and at times, when I read a particularly thoughtful book or research paper, I do think about what I might have achieved if I’d stayed on that ladder. But I also know that what I’ve gained is much richer than what I’ve lost, and I’m glad I got off.

Philip now lives a life that mixes voluntary work in areas to do with mental health with creative writing and research, and takes time to live in the present.

Read more of our Tapestry Stories here.

Illustration by Ethan.