By Kelly Ng //

From how German composer Robert Schumann supposedly achieved superhuman productivity during his manic periods, to what’s been dubbed the “Sylvia Plath effect” – which tries to establish a link between creatives and mental illness based on the life and death of the depressed poem – the theory that creative people are also a little ‘crazy’ has been around for some time.

In recent years, however, some artists – and scientists, too – have cautioned against making the sweeping claim that mental health is negatively correlated with creative inspiration.

Singapore artist Yen Phang is one of them.

Yen, whose art is inspired primarily by biology, including the human body, says the “crazy mad-genius” is a popular myth.

Society must stop thinking about mental health and creativity in two continuous terms, Yen urged.

“If anything, I would like to tell younger artists to disavow themselves of the illusion that one needs to be angsty to be an artist,” says the 40-year-old, who left the legal profession in 2012 to pursue art full time. His artistic practice spans various media, from painting to performance art.

“It’s a romantic notion. I have spent a lot of my life telling people that one doesn’t need to rely on the crutch of this idealised notion of creative genius to do honest and good work. They can influence each other, but the health of one doesn’t depend on the health of the other,” Yen added.

While acknowledging the value of art for creative self-expression, Yen believes that it is not entirely a self-centered pursuit. Artists have a certain level of responsibility to serve the communities they operate in, he said. And because of that, they have to be even more cognizant of their mental health.

“There is responsibility to be a creative person. You are responding to issues of your world. Sometimes, mental illness makes one disconnect from the world. But one needs to open oneself to the experiences of others – to find kindness with oneself, as well, then you can start connecting with the interior experiences of other people. That is how we as artists connect over issues of mental health,” he said.

Yen sees art as a platform to open discussion or evoke certain responses about current issues. Some of his ongoing projects, for instance, look at the interplay between big data and artificial intelligence, with how societies are organized. He is also exploring pieces that speak to changes in our environment, and how they have become more dynamic in this day and age.

“If we can make people give a damn about certain things, if we can allow someone else to pay attention to something they might have taken for granted, and then move the discussion forward… That’s what we, as artists, can do for people,” he said.

That said, the freedom to create – and freedom from pressures of pandering to others’ whims – is key to the artistic process, Yen stressed.

But this can sometimes be found wanting in Singapore, where the education system has often been likened to a “pressure cooker” – a highly competitive, examinations- and grades-focused environment.

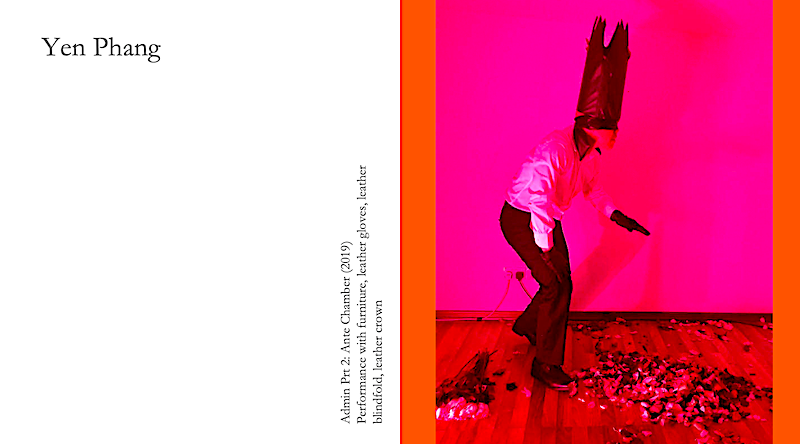

part of The Measure of Things at the Institute of Contemporary Art Singapore

Yen recalls his experience pursuing graduate studies in the arts, when he would sometimes take others’ judgements or suggestions about his work a little too much to heart.

“Sometimes, these are in fact instances of us passing judgement on our own work. We are all aiming for external validation, but this is not always a necessary path of the artist’s process,” he said.

Often, there is also a preoccupation in “finding the correct answers” where there may not be one.

“Elsewhere, people spend time with the artwork first, then say what they feel about the work. In Singapore, there is a need to understand how to correctly interpret the work,” Yen said.

“The one question I encounter the most in Singapore, much more than elsewhere, is ‘What does this mean? Help me understand.’”

With safe distancing restrictions still in place amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, Yen is currently creating from his home – to be specific, his next painting series focuses on his balcony.

“Balconies are a very interesting place for me. They are in between the streets below and the private interiors; and then there’s the curtain for all the drama. But at the end of the day, I’m just painting the florals of my balcony in spring,” he said, noting that spring in most seasonal countries marks a sense of renewal.

Ultimately, artists must learn to trust themselves and the circumstances they have been placed in, to make good with their art, said Yen.

“We have to learn to trust who we are, wherever we are, in our very short time on this world. Let’s listen to the world around us, listen to people around us, but also, most importantly, have a lot of compassion for ourselves as well,” he said.

Yen Phang obsesses upon the biological. He was a recipient of the Winston Oh Grant (2016), Winston Oh Travel Research Award (2016), and was awarded the Cliftons Art Prize (2015) and the UNSW Julius Stone Prize (2006). His work has been collected by the Singapore High Commission in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Singapore), British Airways for their Terminal 1 Lounge at Changi Airport, Singapore. He has also initiated projects such as “I.D. (The Body’s Still Warm)” (2018), Displacements: 13 Wilkie Terrace“ (2013),“The Peony And the Crow“ (2016), and “Repurposing Nostalgia” (2016) under the Displacements banner. Check out his works and work-in-progress on Instagram @yen.phang

Kelly Ng is a journalist and documentary filmmaker in Singapore. A volunteer contributor to The Tapestry Project and the Asian Mental Health Collective, Kelly believes people can start to heal, or fight better for mental health, when they feel heard. She also enjoys distance running, being in nature and has a soft spot for snail mail.

To read more of our Tapestry stories, click here. If you have a story to share, write to us here.